From sheep to sweater

Grades 1 and 2 (Ontario)

Elementary cycle 1 (Quebec)

How can you tell if a fibre is natural or made by humans? Or if it’s wool, cotton or polyester? Students will answer these questions by using their senses and conducting interesting experiments. Through hands on activities, discover the needs and life cycles of animals that are raised for their fibres.

Share :

Printable PDFs

Science and technology

Little lamb

Imagine that your class has been given a lamb. What would this lamb need to survive?

- Ask your students to prepare a list of the lamb’s essential needs. They can begin by filling in the blanks in the “My friend the lamb” activity sheet with words or drawings. Make sure they think about all aspects of caring for a lamb: sheltering it, feeding it, keeping its bedding clean, etc. Ensure that students understand that lambs are not pets, and that they require special care.

- When students have identified what a lamb needs to survive, ask them to compare the needs of lambs and humans. Discuss the similarities and differences. For example, lambs and humans both need to be fed, but do they eat the same things?

Please see the printable PDF for this activity at the bottom of the page.

- Little lamb: Compare the basic needs of lambs and human children

A ewe’s body

Please see the printable PDFs for this activity at the bottom of the page.

- A ewe’s body: Match the correct words to the ewe’s body parts

- A ewe’s body (Answers): Answer sheet for ewe’s body matching exercise

The sheep farmer’s toolbox

Please see the printable PDFs for this activity at the bottom of the page.

- The sheep farmer’s toolbox: Link the items humans need to the corresponding items that sheep need

- The sheep farmer’s toolbox (Answers): Answer sheet for the sheep farmer’s toolbox

A mammal’s life cycle

Students read six paragraphs that describe the life cycle of a sheep. They then cut out the paragraphs, reread them and arrange them in the correct chronological order.

The life of a sheep

It’s springtime. The snow is starting to melt. Every day is a little milder. A ewe gives birth to a lamb. She cleans the lamb with her tongue. Her lamb has a special scent. This scent helps the ewe recognize her lamb. Sometimes ewes have twins and even triplets!

Within an hour of being born, the lamb can stand up. It must find the ewe’s two teats to drink milk. The ewe stays close to the lamb, because it’s very small. She protects it, keeps it warm and makes sure it can drink whenever it’s hungry.

When the lamb is a week old, it can venture farther away from the ewe. There are many other lambs in the flock. They like to play and explore together. After their adventures, each lamb returns to its mother.

It’s hot! Summer has arrived. The lamb has grown a great deal. It’s now called a sheep. It hardly drinks any milk at this stage, so the ewe produces less and less. The sheep now eats hay. It also likes to eat grass and grains, such as oats or corn.

The leaves are falling and it’s getting cooler. Fall has come. The sheep is eight months old. It’s now an adult! It is large and strong enough to look after itself. This adult sheep is male and so it’s called a ram. An adult female is called a ewe.

For the ram to become a father, it must meet an adult ewe. The lamb grows in the ewe’s womb. It takes five months for it to develop. Like its parents, the lamb will be born when winter is over.

Other suggestions

- Students can show that they have understood the text and learned the vocabulary by answering the questions on the ‘Mammal’s life cycle’ activity sheet

- Students can create a poster about the life cycle of sheep, using their own drawings or finding images on the Internet to illustrate the stages. Using a large sheet of paper, they can arrange the pictures in a circle then write labels to identify each stage and draw arrows to connect them. See the Bombyx mori moth diagram under ‘An insect’s life cycle’ as an example.

- As a group, compare the life cycle of humans and sheep, identifying similarities and differences (For example, a similarity: babies and lambs both drink their mothers’ milk; a difference: humans’ developmental stages are much longer than those of sheep)

- Compare the life cycle of sheep with that of silkworms

Please see the printable PDFs for this section at the bottom of the page.

- A mammal’s life cycle: Arrange the steps in a mammal’s life cycle in the correct order

- A mammal’s life cycle (answers): Answer key for A mammal’s life cycle activity

- A mammal’s life cycle (reading comprehension): A short exercise to verify comprehension of the life of a sheep

An insect’s life cycle

Bombyx mori moth (silkworm)

The bombyx mori is a moth. The female lays between 300 and 500 eggs on the leaves of the white mulberry tree. The eggs hatch 10 to 14 days later. We call the larvae, or caterpillars, of this moth “silkworms”.

Silkworm caterpillars eat mulberry leaves for about one month. This is the longest stage in the insect’s life cycle. To grow, the silkworms must moult, or shed their skin, four times. They will grow to 7.5 centimetres in length.

Each silkworm spins a cocoon of silk. It produces the silk using special organs in its mouth. Inside the cocoon, the larva transforms into a chrysalis.

The metamorphosis takes two weeks. The moth then emerges from the cocoon. A female must meet a male to be able to produce eggs. This last stage is very short. Because the adult moth has no mouth, it cannot eat and it dies within a few days.

Please see the printable PDF for this activity at the bottom of the page.

- An insect’s life cycle: Arrange the steps in a insect’s life cycle in the correct order

What’s natural

In this series of activities, students will consider some of the big questions surrounding Canadian agriculture.

Please see the printable PDF for this activity at the bottom of the page.

- What’s natural?: Distinguish the elements that are found in nature or made by humans. Circle the items that are found in nature. Draw a triangle around the ones that are made by humans.

| Natural | Made by humans |

|---|---|

| skeleton | steel beams |

| feather | plastic bag |

| honeycomb | socks |

| stone | tire |

| deer antlers | sweater |

| shell | house |

| stick | juice box |

| nest | vase |

Other suggestions

- What’s found in nature can be used as material. Ask the students to imagine that they are travelling on a ship that runs aground on a desert island. Using natural items they find there, the students have to build a house. Ask them to draw a picture or build a model of the structure they conjure up.

- Take the students into the schoolyard on a treasure hunt for natural materials

- Ask the students to choose a manufactured article and to research the materials it is made of and how it was put together. The Internet offers many videos that explain the process of materials being made into articles.

Exploring properties of fibres

Fibres are an important material in manufacturing articles, but not all fibres have the same properties. In this experiment, students create a profile of the observable properties of the fibres that make up specific articles. In doing so, they will discover the vocabulary used to describe properties and learn to use their senses to gather data.

Materials

Ask the students to help you by bringing to school various garments and other articles made from fibres, or use garments from the locker room and other articles at hand.

Examples could include an umbrella, mitts, a scarf, a fleece garment, a sweatshirt, socks, a baby blanket, a sports sweater, a towel, a hat, a bathing suit, a windbreaker, footwear, pyjamas, jeans, a tent, a kite, a chalkboard eraser, a carpet, a raincoat and nylon stockings.

Instructions

- Discuss with the students how garments and articles made from fabrics have different purposes (some absorb, repel or allow water to evaporate; some keep a person warm, cool or comfortable; others allow the wearer to stretch and move easily). Explain that a material must have certain properties if the article it is made into is to be functional.

- Divide the students into small groups and give each group an article made from one or more Ask the students to use their sense of touch, vision, smell and hearing to examine the materials that make up the article. They should then answer the questions on the worksheet to create a profile of the properties of the fibre examined.

Other suggestions

- After this experiment, gather the articles and put them on view for all the students to In turn, each group describes the properties of the article it has examined, without naming the article. The other students try to guess the mystery article by looking at, handling and sorting all the articles on show.

- Ask the students to sort the articles by function and to compare the fibre properties of articles in the same category and in different Ask them about any trends they observe.

- Read any labels on the articles to find out the names of the fibres used to make Using a bar chart, help the students identify which fibres are used most often.

- List some properties of fibres. Then ask students to present these properties to the class in the form of a collage of pictures cut out from catalogues, magazines and flyers and illustrating articles made from different For example, a student could use a picture of a bathing suit to represent elasticity or a baby blanket to represent softness.

Please see the printable PDF for this activity at the bottom of the page.

- Exploring properties of fibres: Determine the properties of different materials

Mathematics

Please see the printable PDFs for this section at the bottom of the page.

- Count the sheep: A counting activity involving lambs, rams and ewes

- Complete the series: A sheep and wool patterning activity

- Fleece for sale: Draw coins to show how much money the farmer receives for each fleece sold.

- In the sheepfold: Solve math problems by using objects to represent sheep

- An alpaca with an appetite: Map out how to help an alpaca reach a tasty apple

Language

Please see the printable PDFs for this section at the bottom of the page.

- What am I?: Solve the riddles and determine the identify of mystery fibres

- What am I? (answers): Answers for What am I? activity

- Word search: Hunt for words related to natural and synthetic fibres

- Word search (answers): Answers for Word search

- Word scramble: Rearrange the letters to discover some sheep products and by-products

- Word scramble (answers): Answers for Word scramble

Arts

Finger weaving

First Nations in North America have been finger weaving for a long time. They used this form of weaving to make objects such as belts. The belts could be used to pull toboggans and to carry heavy or bulky loads.

When Europeans arrived in North America, they began to trade goods and exchange knowledge with the First Nations. One exchange was wool blankets for beaver pelts. The First Nations would unravel the blankets to obtain wool yarn, which they found to be very useful. They also discovered that articles made from wool were more water-resistant, suppler and more durable than those woven from their usual materials.

For their part, the French quickly learned the art of finger weaving and began making what we know as ceintures fléchées, or arrowhead sashes. Men wore these long, colourful sashes around the waist to keep their coats or shirts closed when the weather was very cold. Coureurs des bois and Voyageurs also wore arrowhead sashes. They needed to lift heavy bales of fur, and the sashes kept them from injuring their stomachs and backs. They also kept them warm, since they were made of wool. And the sashes stayed dry and lightweight, even in snow.

Today, arrowhead sashes are a very important cultural symbol for the Métis in western Canada. In eastern Canada they represent, more broadly, French-Canadian, Acadian and First Nations cultures. There are still many artisans who make traditional sashes using finger weaving. And Quebec City’s Bonhomme Carnaval is proud to show off his arrowhead sash!

Weaving students

This exercise illustrates the process of weaving strands of fibre into fabric. The art of weaving has played an important part in the history of civilization.

Materials

- Roll of toilet paper or crepe paper

- Magnifying glass

Instructions

- Ask the students to examine samples of woven fabric, such as burlap, using a magnifying glass, then ask them to describe what they Explain that, in manufacturing fabric, fibres are first twisted together to form strands, and the strands are then woven into cloth. In weaving, horizontal (or weft) strands cross vertical (or warp) strands in a sequence.

- Invite the students to make themselves part of a weaving as a means of understanding how the process works. Ask between five and ten students to stand next to each other in a line, with a little space between them, and to keep still. Instruct the first student in the line to hold the end of the paper strip and not to let go of it.

- Unroll the paper strip behind the first student, in front of the second student, behind the third student and so on, until you reach the last student in the line. Take the strip around the last student, and then return to the starting point, continuing to unroll the strip between the students.

- Repeat the process a few times so that the students can see that they are now held together by the paper strip. Explain that they form what is known as the warp and the paper strip forms the weft.

Other suggestions

In small groups, the students can practice making themselves into weavings using toilet paper or crepe paper strips. Organize a race to see which group can weave themselves fastest.

On the Internet, research weaving techniques and tools used now and in the past (for example, finger weaving and the use of the backstrap loom, vertical loom and industrial loom).

Finger weaving activity

Weaving is one of the oldest methods of producing textiles. First Nations developed finger-weaving techniques hundreds of years ago, to make the articles they needed. It’s an art form still practiced today. In this activity, students learn finger weaving by making a traditional bracelet. Before they begin, read the short overview that explains the importance of finger weaving in Canada’s history.

Materials

- Wool yarn in five different colours, cut to the length of the forearm

- Sticky tape

Instructions

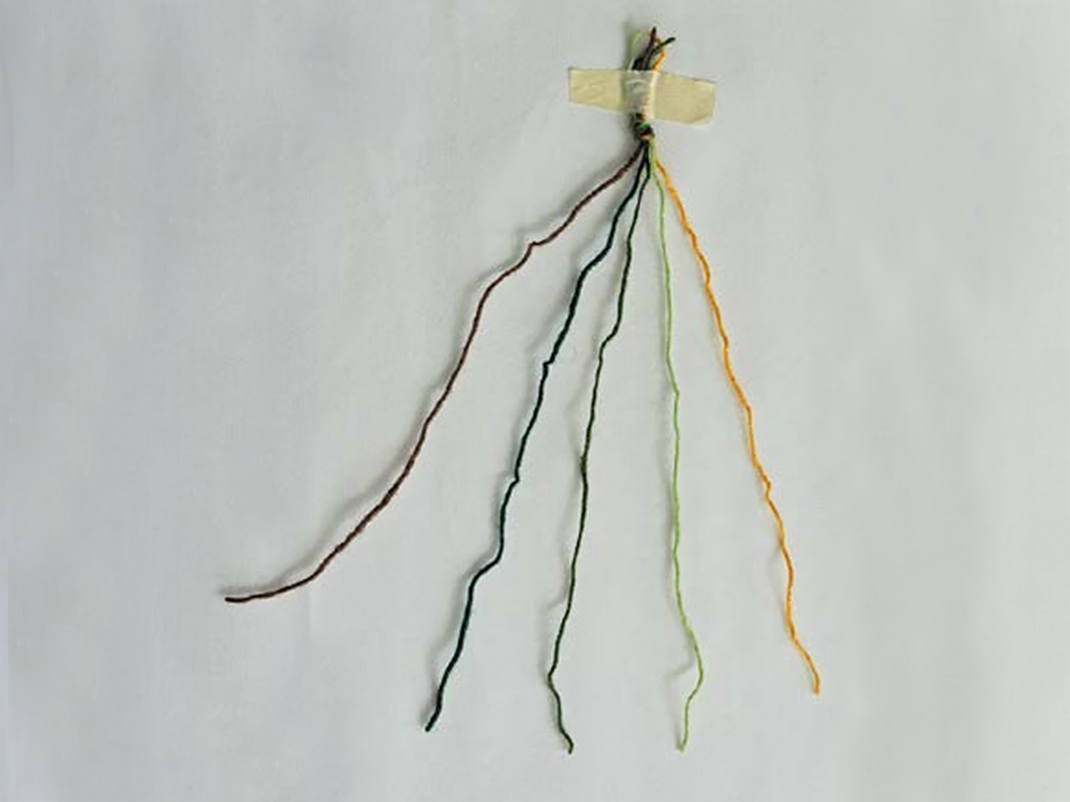

- Tie one end of all the strands. Use sticky tape to attach the knot to the work surface. Separate the strands and note the order of the colours. Follow this order throughout the activity. If necessary, attach the free ends of the strands to the work surface to keep them in order.

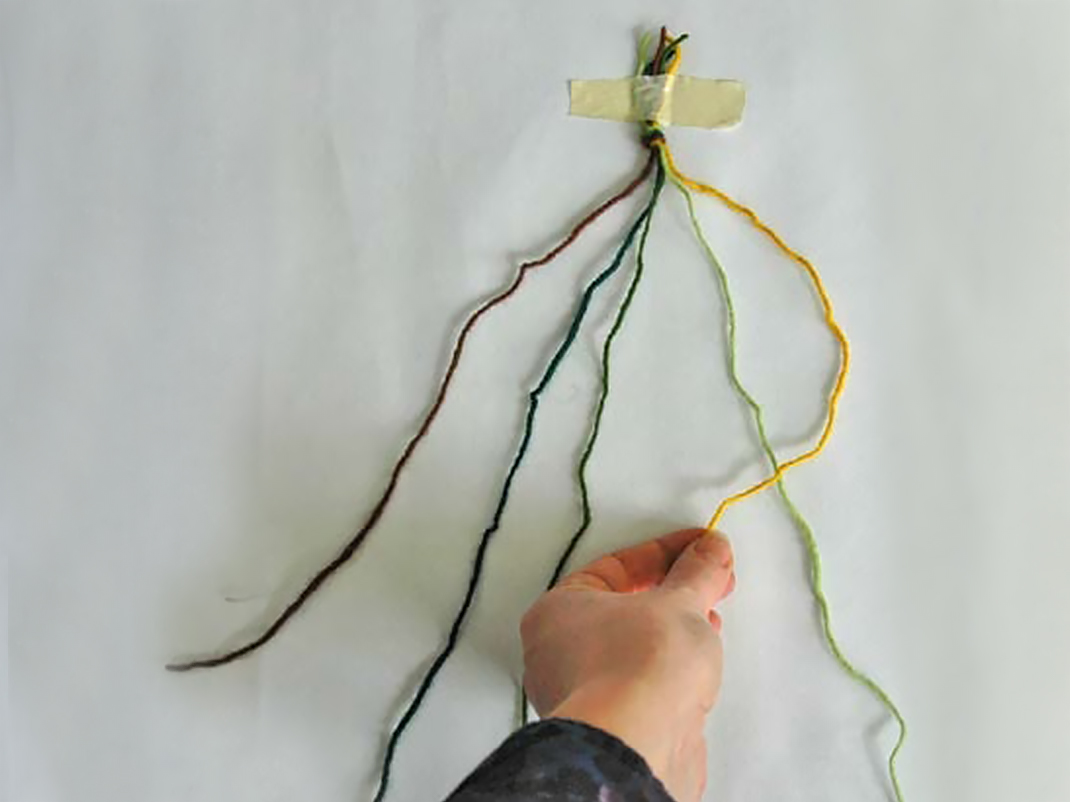

- Take the first strand on the right (yellow) and pass it over the strand immediately to its left (lime green).

- Continue to weave, passing the yellow strand under the next strand (forest green). Alternate weaving over and under until you reach the last strand on the left.

- With the ends of the strands attached to the work surface, it is easy to adjust the tension of the weft (horizontal) strand by pulling it gently upward and to the Attach this strand to the work surface.

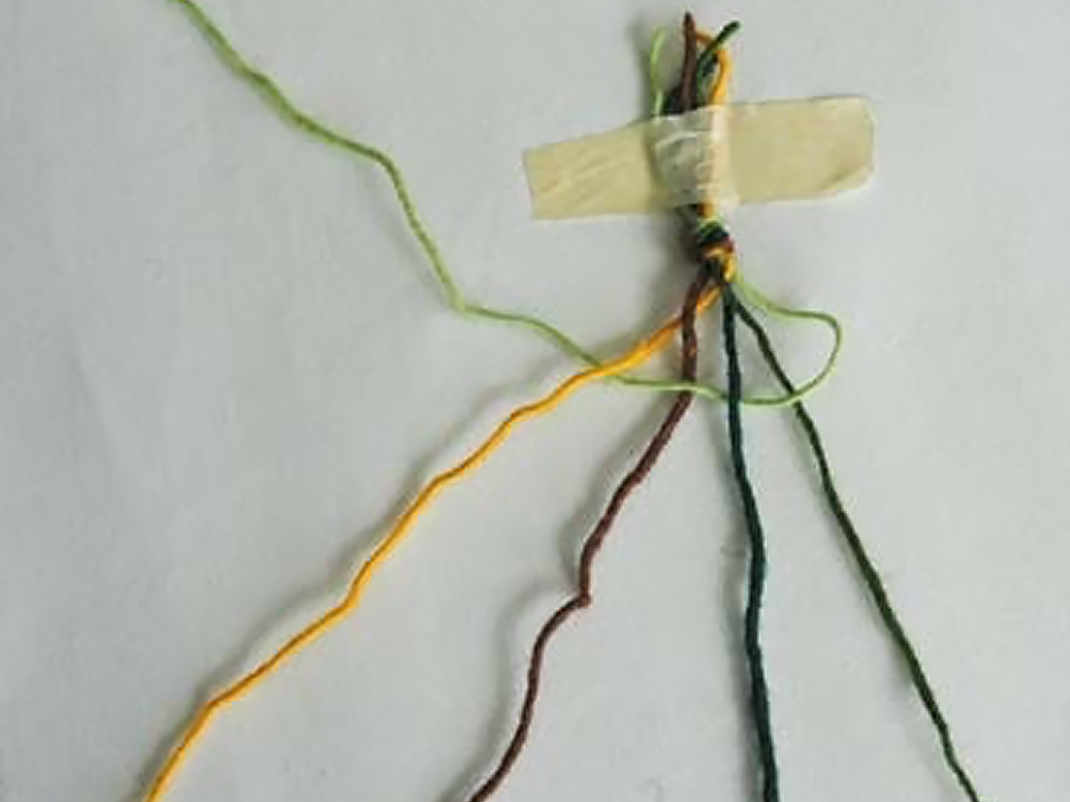

- Begin the process again, using the strand that is now the first strand on the right (lime green).

- Continue in the same way until the bracelet is long enough to be tied around the wrist. Tie a knot in the strands so that the weaving cannot come undone.

Felting

Sheep’s wool has its own unique property: it can be felted. No other fibre can be made into real felt. Felting compacts the wool, increasing its insulating value and making it sturdier and more water-resistant. With this craft, students feel the wool in their fingers turn into felt.

Materials

- Carded wool

- Sample of felted wool

- Basins (large, flat bottomed for warm, soapy water

- Mild liquid dish detergent or bar of soap

- Scissors

- Green pipe cleaners (short and long)

- Green baize (soft, thin sheet of wool felt

Instructions

A few days before the activity

- Ask students to bring a small ball (about 3 centimetres in diameter) or other round object, such as a pebble or large marble, from home. This object will serve as the flower mould.

Introduction to craft

- Pass around the samples of loose wool and felted Ask the students how they think wool is made into felt.

- Explain that felting is an ancient practise. Show the photo of wool fibre taken with a microscope. Explain that wool can be felted because it is covered with tiny scales.

- It takes moisture, friction, and pressure to felt wool. Wool fibre is covered with tiny scales that overlap one another, like the shingles on a roof. When wool becomes wet, the scales lift and the fibre swells. If the fibres are rubbed together, they become tangled and the scales hook on to one another. Heat accelerates this phenomenon. When wool dries, the scales close, clamping tight around the fibres they are tangled with. Felting compacts wool, making it less permeable, a better insulator, sturdier, and more water-resistant. Once it has been felted, wool remains that way.

Craft – Felt flower

Part 1

- Set up felting stations — one for every 4 or 5 students, on desks or tables.

- Place a basin of warm, soapy water at each station. The warmer the water, the faster the felting will go.

- Cover each ball evenly with three thin layers of carded wool. Place the layers perpendicular to each other so that the fibres overlap in different directions.

- Soak the ball in the water, and then squeeze the water out. Place one or two drops of liquid soap in the students’ hands (or use a bar of soap) and have them rub their hands together. The soap helps to wet the wool and opens its scales. It also acts as a lubricant and keeps the wool fibres from snagging their skin.

- Roll the ball between the hands or against the table until the wool is felted. This will take a few minutes. If the ball cools off, soak it and roll it again. The more movement and pressure, the faster and more compact the felting will be.2

- Once the wool is felted, rinse the ball, and squeeze out any remaining water. Snip out a little wedge in order to be able to remove the mould. Cut petals (3 to 5), working from the snip. The students will probably need help making the snip and cutting the petals. Adult supervision is advised. Open up the petals and place them in the desired position. Allow to dry. Felted wool retains its shape while drying.

- While the flower is drying, cut two leaf-shaped pieces from the baize. The students can copy a model, or cut any shape they like.

Part 2

- When felting has dried, have students collect their flowers and leaves, as well as one long and two short pipe cleaners.

- Use a pair of pointy scissors to make a small hole in the centre. The hole is where the stem will be attached. Adult supervision is advised for this step.

- Pass the long green pipe cleaner through the centre of the flower. Twist the end of the pipe cleaner into a little knob to keep it from slipping out. Use the short pipe cleaners to attach the felt leaves to the stem. The flower is finished. What a nice gift for someone!

Resources

Additional information

What is a material?

A material is a substance of natural or artificial origin that has specific properties and is used to make objects. Wool is a material of natural origin: it consists of sheep’s hair.

What is an object?

An object is something that is designed, processed, or manufactured to serve a specific function. An object is made of one or more materials. For example, a mitten made of wool is an object.

An object can also be something more complex, made by combining two or more objects. A sweater that is made from knitted wool yarn and has a zipper and buttons is an example of a more complex object.

A material can also be an object

When a material is used to serve a specific function, it becomes an object. For example, felted wool used as a blanket is an object. Felted wool cut up and sewn into slippers also demonstrates how a material is transformed into an object.

Wool …

… resists static electricity

Because wool fibres absorb the moisture in the air, they build up very little static electricity. So wool clothing clings less to the body, and has less tendency to cause sparks, or attract lint or dust, than clothing made from other types of fibres.

… is flame resistant

The presence of water and keratin (the protein that is the main component of wool fibre) make wool a naturally flame-resistant fibre. Wool must reach a higher temperature than most other fibres in order for it to burn. When it does burn, wool combusts slowly and generates little heat. A wool blanket is on effective way to extinguish a flame.

… is elastic

Because of its shape and structure, wool fibre is elastic. Each fibre is made up of long chains of amino acids (proteins) that are naturally coil-shaped. Like a coil, wool clothes that are stretched or compressed resume their initial shape when the pressure is released. This property also keeps wool clothing from creasing.

… resists odour

Because it is not conducive to the growth of odour-causing bacteria, wool does not retain odours. Unlike a cotton or polyester sweater, a wool sweater will not smell unpleasant after a weekend of hiking or camping.

… absorbs dye

Wool fibres have tiny microscopic pores that enable them to absorb not only moisture from the air, but dye, too. Wool can be dyed every imaginable colour, making it a favourite fibre for making colourful clothing. The colour of the wool changes very little over time. Unlike cotton, it does not fade when washed or when exposed to sunlight.

Natural, Synthetic or Artificial?

There are two main categories of fibres: fibres of natural origin (natural fibres) and fibres of chemical origin (chemical fibres). Natural fibres, such as cotton, silk and linen, are fibres we find in nature; they are produced by plants and animals. Chemical fibres are those we manufacture, using chemical processes to transform natural substances. Chemical fibres have two main subdivisions: synthetic fibres and artificial fibres.

Nylon, polyester and acrylic are synthetic chemical fibres. They are made from fossil fuels (oil and coal). First, these raw materials need to be transformed into plastics. Then, to manufacture the fibres, the plastic is heated to form a thick paste, which is then put through an extruder. An extruder resembles a garlic-press. This machine pushes out thin threads, which are then cooled, stretched and processed further. Nowadays, most polyester is made from recycled plastic bottles.

Artificial chemical fibres, such as rayon, bamboo and corn fibre, are formed like synthetic fibres. However, the raw material used is cellulose, which is extracted from the plant material. The cellulose is chemically transformed into a paste. Tiny fibres are formed by the extruding process. These are then put in an acidic solution to harden. Milk fibre is another artificial fibre which is formed by extrusion. In this case, a protein called casein is isolated from milk and is transformed into a paste. This fibre is soft, hypoallergenic and absorbent.

Chemical fibres are less expensive than natural fibres, and can imitate expensive natural fibres like silk. But synthetic fibres are not biodegradable and do not have the same properties as the natural fibres they imitate.

Fun facts

- For years fishermen around the world have worn wool garments to keep themselves warm during cold days and nights at sea!

- A long time ago, until the 1940s, bathing suits were made from wool! However, because wool is so absorbent, it is difficult to swim in a woolen suit because it becomes heavy when wet. Wool is so absorbent it has even been used to trap oil after environmental disasters such as an oil spill.

- Baseballs are filled with It takes 137 metres of wool to fill a baseball!

- A sheep grows an average of 6 kilograms of wool each year

- If the fleece of one sheep was spun into a single length of yarn, the strand would reach from Ottawa to Montreal—over 200 kilometres!

- Australia produces the most wool, while China is the top consumer of raw wool in the world

- Scientists have found 34,000-year-old twisted wild flax fibres in soil samples taken from a cave in the country of Georgia. These are the earliest evidence of humans using fibres as materials.

- Humans have been practicing agriculture for about 11,000 years. Sheep were among the first animals to be domesticated.

Glossary

Alpaca (noun)

Domesticated South American ruminant mammal of the Camelidae family, raised for its long, woolly fleece

Article (noun)

Solid object, considered as a whole and manufactured for a specific purpose

Artificial (adjective)

Made by human skill as opposed to by nature, an imitation

Billy goat (noun)

Male goat

Bleat

Sheep’s cry (n.); to make a sound like a sheep (v.)

Breed (noun)

Subdivision of an animal species (for example, the poodle is a breed of dog)

Buck (noun)

Male goat

By-product (noun)

Product derived from another product (wool is a by-product of sheep raised for mutton)

Carnivore (noun)

Organism that eats only flesh (meat)

Chrysalis (noun)

Pupa of moths and butterflies that is inactive and enclosed in a firm casing from which the adult eventually emerges

Cria (noun)

Baby alpaca

Doe (noun)

Female goat

Dye (noun)

Colour with a colouring agent that results in a predetermined colour

Electric shears (noun)

Equipment used to shear sheep

Ewe (noun)

Female sheep

Fibre (noun)

Long, fine element of natural origin or made by humans

Fleece (noun)

Coat of sheep’s wool removed by shearing

Flock (noun)

Group of sheep

Goat (noun)

Leaping and climbing ruminant mammal of the Caprinae family, raised for its milk, meat and sometimes for its fleece

Grass (noun)

Grasses that livestock eat in the pasture

Guard animal (noun)

animal whose job it is to protect a flock of sheep from predators

Hair (noun)

Threadlike (long and fine) outgrowth on the skin of mammals

Hand shears (noun)

Large scissors used to cut sheep’s wool

Hay (noun)

Crops (grasses or legumes) that are cut, dried, and stored for use as food for livestock

Herbivore (noun)

Organism that eats only plants

Herding dog (noun)

Dog that protects a flock of sheep or keeps it together

Herdsperson (noun)

Person who feeds, cares for, and manages animals

Horn (noun)

Hard, often pointed outgrowth on the head of many ruminant mammals

Larva (noun)

Form of insects when they hatch from the egg

Lamb (noun)

Baby sheep

Mammal (noun)

Class of vertebrate animals that feed their babies milk

Material (noun)

Anything that serves as raw or crude matter to be used or developed, Substance used to make articles

Meat (noun)

Animal flesh

Milk (noun)

Fluid secreted through the mammary glands of female mammals to feed their young

Moult (verb)

In animals, to renew skin, feathers or fur as a result of growth, age or environmental conditions

Nanny goat (noun)

Female goat

Natural (adjective)

Existing in or formed by nature

Nutritious (adjective)

Containing an abundance of nutrients

Oats (noun)

Cereal plant whose seeds (grains) are used to feed livestock and humans

Object (noun)

Anything that is visible or tangible and is relatively stable in form

Omnivore (noun)

Organism that eats both plants and meat

Pasture (noun)

Where livestock eat plants growing on the land

Predator (noun)

Animal that eats prey (other animals

Prey (noun)

Living thing that an animal preys upon in order to eat it

Property (noun)

Characteristic of a thing that distinguishes it from other things; particularity

Pupa (noun)

Inactive form of insects of the Lepidoptera order: stage between the caterpillar and the adult butterfly

Ram (noun)

Male sheep

Ruminant (noun)

Mammal having a stomach that is divided into several compartments

Scent (noun)

A distinctive smell (in the case of sheep, enables the animals to recognize each other)

Shear (verb)

To shave a sheep to remove its wool

Sheep (noun)

Thick-haired ruminant mammal of the ovine species, raised for its wool, flesh, hide, and sometimes its milk

Sheep barn (noun)

Building that houses sheep

Shepherd (noun)

Person who watches over and tends to a flock of sheep

Spin (verb)

To twist fibres to form a thread

Strand (noun)

Small bit of spun wool

Straw (noun)

Grain stalks used as bedding for farm animals

Synthetic (adjective)

Produced by synthesis, that is, the preparation of a chemical compound from its constituent elements

Printable PDFs

Activity sheets

- Little lamb (PDF, 224 KB)

- A ewe’s body (PDF, 929 KB)

- A ewe’s body (Answers) (PDF, 819 KB)

- The sheep farmer’s toolbox (PDF, 697 KB)

- The sheep farmer’s toolbox (Answers) (PDF, 709 KB)

- A mammal’s life cycle (PDF, 1 MB)

- A mammal’s life cycle quiz (PDF, 190 KB)

- A mammal’s life cycle (Answers) (PDF, 266 KB)

- An insect’s life cycle (PDF, 478 KB)

- What’s natural? (PDF, 390 KB)

- Exploring properties of fibres (PDF, 497 KB)

- What am I? (PDF, 2 MB)

- What am I? (Answers) (PDF, 187 KB)

- Word search (PDF, 324 KB)

- Word search (Answers) (PDF, 610 KB)

- Word scramble (PDF, 403 KB)

- Word scramble (Answers) (PDF, 414 KB)

- In the sheepfold (PDF, 202 KB)

- An alpaca with an appetite (PDF, 837 KB)

- Count the sheep (PDF, 841 KB)

- Complete the series (PDF, 289 KB)

- Fleece for sale (PDF, 591 KB)

Colouring pages

- Colouring page 1 (PDF, 786 KB)

- Colouring page 2 (PDF, 313 KB)

Acknowledgements

Photos of fibres under scanning electron microscope produced in collaboration with Milosav Kaláb, Ph.D, Honorary research associate at the Eastern Cereal and Oilseed Research Centre (ECORC), Agriculture and Agri-food Canada, in Ottawa, Ontario – do not reproduce without permission.

You may also be interested in

Meet the farm animals field trip

Students will smell, touch, observe, and listen to a variety of farm animals—up close and personal!

AgVenture: From sheep to sweater

How did pioneers turn a sheep’s fleece into clothing? This flexible program will allow your students to explore the properties of wool through fun activities.

Virtual field trips

Bring the museum to your classroom with bilingual, curriculum-linked programs for all grade levels that allow your students to discover various STEM topics.